Guest post by Zainab Kizilbash Agha

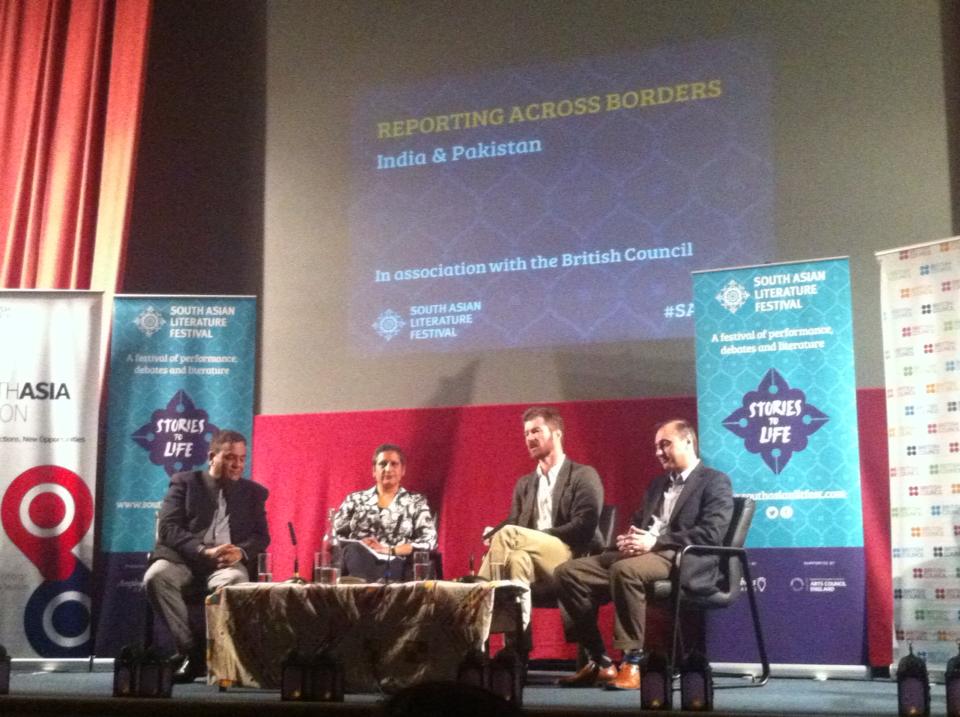

Panel: Amit Chaudhuri (author, Professor of literature at East Anglia) and Jeet Thayil (poet, author, musician)

Moderated by: Ted Hodgkinson (British Council Literature)

Date: November 1st, 2013

The South Asian Literature Festival ended its 2013 programme with an event interestingly titled as ‘Addictive Cities’. There are some cities – cities like Calcutta, Karachi and Bombay – that have drawn writers back repeatedly and that have helped writers tell the stories they want to tell, while in turn the writers have wound up telling the stories of the city.

Even though it was a particularly wet evening, and a Friday, the room was filled to capacity with people in welly boots, waterproof jackets and slightly wet green saris. In the session, a little longer than an hour, Ted Hodgkinson conversed with two authors who have had particularly monogamous relationships with their cities: Amit Chaudhuri, author of various books set in Calcutta including The Immortals of Calcutta; and Jeet Thayil, poet and author of Narcopolis, which is a story of Bombay experienced through opium addiction.

Ted cleverly used the mundane details of life in each author’s writing to engage with them on bigger ideas – identity, religion, modernity and Indian cosmopolitanism.

Both authors agreed that they liked to ‘flip’ reality in their writing and show readers a different perspective on things. For example, both tended to show the urban, man-made landscape as more natural than the rural one. For Jeet, this battle between urban and rural was like a match between the writings of Baudelaire and Wordsworth. The city won, he said, because only it could make people truly anonymous, and therefore it was ‘the only place where freedom was possible’. Bombay, in particular, interested Jeet because of the way the city warmly accepted all kinds of people in a truly democratic way, rewarding nothing but talent.

To explain his fascination with Calcutta, Amit read a passage that praised the city’s essential modernity, talking about the sense of timelessness that Calcutta embodied – not in the grand, formal way of mausoleums, but embedded in the patina that covered the streets, in its ‘aura of decay’ and the ‘slated windows that have stood forever’. “True modernity is not anything new,” he pointed out.

Jeet also read part of the prologue to his book, which started with ‘Bombay, which obliterated its own history by changing its name […]’. He rejected the use of Mumbai, he explained later in response to a question, because it was a deliberate political construct by people ‘who don’t read books and never will’. Amit added to this by explaining that the word ‘Kolkata’ did not exist in English other than as a utopian literary term just like ‘Calcutta’ seemed to have no meaning in Bengali.

The conversation continued on many different themes, one of them being the defining characteristics of good writers. According to Jeet, romantic poets were particularly to blame for making writers believe that they had to live a certain lifestyle – full of blistering relationships, drugs, alcohol and an assortment of other addictions – to be able to write, with the result that they become too busy leading that life to actually write. He read out a poem he wrote as a letter to Baudelaire after he won over his twenty-year drug addiction, admonishing the French poet for pushing him towards drugs. Ted offered him the poem on a paper to read out. Jeet declined and read it from memory and the audience got to see the performance poet at his best. There were laughs as Amit checked his recitation against a copy of the poem on a page in front of him.

The evening ended with a question about Calcutta and what the city meant for the Bengali identity. Amit said that as a child, Calcutta would speak to him about his Bengali identity through children’s fiction. He went on to explain how many serious writers of adult Bengali fiction, including Tagore, wrote a quota of children stories. This project to invest in Bengali children’s literature began in the 19th century and stretched ‘till today. Indeed, what better wayto help a child’s identity develop than through good stories? A future DWL project perhaps, I thought, as the evening and the Festival closed with promises of more to come next year.

Zainab Kizilbash Agha works in the public sector trying to improve how governments spend money and the choices they make. She has worked with governments in Pakistan, Namibia, Ghana and now works in the UK. She writes for therapy. Some of her rants are here: