For the last 5 weeks, I have been teaching a poetry course through Desi Writers Lounge. It is a basic, sweeping course, titled “Elements, Themes, and Form.” We have talked about things like imagery, abstraction, figurative language, and the salient themes in poetry: self-portraits and, begrudgingly, love. This is not to say that poetry is limited to these two themes. On the contrary, I feel it is the most natural form of expression for any emotion. However, when one first starts to dabble in poetry, one is, more often than not, naturally drawn towards these two themes.

For the course, I have re-read some of my favorite poems and have had the pleasure of composing discussion questions based on the weekly reading. Last week we were exploring the theme of Love and Desire, and it corresponded with the highest number of assigned readings for the entire course. We read the following poems, which I highly encourage everyone to get their hands on, like, right now.

– Li-young Lee, “This Room and Everything in It”

– Joy Harjo, “The Real Revolution is Love”

– Sandra M. Gilbert, “Anniversary Waltz”

– Richard Ronan, “Soe”

– A. Loudermilk, “Daring Love”

– Chitra Divakaruni, “Sudha’s Story”

– Sheila Zamora, “In Return”

– Nhan Trinh, “Country Love”

All three of the course participants were also given homework, which was to write an original poem on the theme of love and desire. It was an open prompt and they were told to use the week’s reading as inspiration.

I got three very different poems.

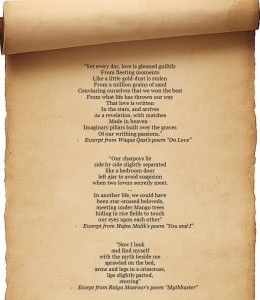

Waqas A. Qazi wrote a jaded poem titled “On Love.” He was also not a fan of the readings – a curious response as he has appreciated all the assigned poems in the past. “I don’t quite know what to make of this week’s readings. I think one needs to be in a specific kind of mood to read and appreciate romantic poetry. This has not been one of those weeks. Hence my interpretation of these poems may be quite subjective. I don’t think there is a poem here which has really impressed me yet,” wrote Waqas. I am not going to lie – the bitter honesty in his words crushed me! Lee’s “This Room and Everything in It” is one of my favorite poems and I have used it as a motif to write a poem myself, which in my opinion, is some of my more polished work.

The response from the other two course participants was encouraging. Hafsa Malik wrote, “Okay, so love is a hackneyed theme, I agree, but to sound like a bit of a cliché myself, I am a hopeless, hopeless romantic. So I really love good love poems! You should have totally included Brown Penny in this [by the way], Noor. A gem, that poem is.” I agree. I should have included “Brown Penny” by Yeats, a poem that remained my signature on the Desi Writers Lounge forums for a few years. Hafsa wrote a poem about love and longing, beautifully evocative, titled “You and I.”

Raiya Masroor also said something after my own heart. “The poems in this selection deal with this clichéd theme in a realistic way. Most of the poems are about real love, loss, and desire instead of focusing on the beloved, his/her characteristics, and the waiting/pining for a lover. They deal with the concept of love in real lives.” Raiya really hit the nail on the head, I think. It’s the simple and frightening reality of love in these poems that makes them so compelling to read, in my opinion. Raiya’s own poem, a remarkably well-written piece about finding bliss in a relationship, seeing love in the simplest of acts once you discover and possess it (like the snores of your partner), was absolutely brilliant and a testament to the fact that not all thematic poems on love have to be long, torturous, drawn-out cliches. She intriguingly titled her poem “Mythbuster.”

Reading through the work of these three poets, each with a very different approach towards and perspective of love and its perils, I thought about the poems I have written on the subject. They have been few and far between, but they have definitely portrayed more of the weary frustration reminiscent of Waqas’s “On Love” rather than Hafsa’s longing in “You and I,” and they have certainly never been as obviously blissful as Raiya’s “Mythbuster.”

Last week we read about love, we talked about love, but I have come to believe that all poetry ever written has barely just scratched the surface of this compelling theme. In the pleasant deluge of poetry on love and desire that I immersed myself in last week, I kept circling back to the two lines of wisdom that (to me) represent a universal truth about this reckless emotion, penned by the great W.B. Yeats:

“Ah, penny, brown penny, brown penny

One cannot begin it too soon.”

So, in talking about love, I did not discover anything more than I already knew. And I was reminded of the fact that I really don’t know much about love at all.

Looking through my work from years ago, my very first poetry workshop to be exact, circa 2006, I found two short poems in an old chapbook. They must have been written in response to a similar prompt, a prompt related to love, which is why the poems are so succinct and, quite frankly, stiff-necked, opinionated, rigid, but at the same time, they are fascinating specimens that bring to light the state of mind of the 21-year-old Noor.

I am going to leave you with these specimens now. Not my best work by any stretch of the imagination, but here it is for what it’s worth. Two poems from October 2006.

Crossroads

We are at the place

where it is easier to hate

than to love each other.

Synonyms

He calls me,

I answer,

as much out of duty

as out of love.

And after the sheer humiliation that comes with posting the two poems above, I am compelled to post something recent that is more representative of my present poetic voice, loosely related to the theme under discussion.

Hand in Hand

we are on our travels with

undercurrents of conversation,

promises cracked through the middle,

wrapped in the cloth that blinds us

there are so many realities of us,

a decade full of crests and troughs,

a steady progression of waves and bodies,

flesh loosening,

aging,

the crow’s feet around my eyes,

the subtle lethargy in my breasts,

and you look new still

you have come and gone

like a song that disappears

as a car with the radio blaring

passes us by on the open road

now, after sheltering my body

in the fetal position,

broken wholly in some places

and incompletely in others,

I wonder if dignity,

(the price of this compromise)

is to be eaten for dinner

to fill up my stomach

that knows no sin,

and if the measure of my affection

is how much I have cried

let’s take a diverging walk now –

some furlongs on foot

and you will meet a small gap in the asphalt,

we can fall through it and come out

on the other side –

one lurch and a blink,

and we will cross oceans and icebergs

to be reborn –

ourselves again

in the native land,

our eyes feasting

on cotton crops and sugar cane and

tilled fields

you say nothing –

it’s just as well,

here, on our journey,

language has no power

and we haven’t crossed over yet

two thousand ears of corn,

two thousand ears

scattered in the ocean

their tympanic membranes

vibrating still,

and voices taking shape,

murmuring like ghosts lazing on the waves

the darkest place I have been to

is this ocean at night, with you,

we are on our travels still,

we are on our travels

Disclaimers

1. The title is stolen from Raymond Carver’s excellent short story, What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. I highly recommend it!

2. This post originally appeared on the author’s personal blog, Goll Gappay – Little Matters That Matter.

Notes

1. If you’d like to join Desi Writers Lounge, a platform dedicated to coaching new writers and poets, please complete the registration form here. The writing sample is important. We do screen our applicants, so please be sure to provide one.

2. All of us at Desi Writers Lounge work very hard to create a bi-annual online literary magazine called Papercuts. Browse through our hard work and let us know what you think on the Desi Writers Lounge Facebook Page or leave comments on the webpage.

3. If you haven’t done so already, like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter