by Zainab Kizilbash Agha

‘What really knocks me out is a book that when you’re all done reading it, you wish the author that wrote it was a terrific friend of yours and you would call him up on the phone whenever you like it. That doesn’t happen much, though.’ J D Salinger

Yes. How nice if we could pick up and call Jane Austen to ask for Mr. Darcy’s number or ask Yann Martel to end our misery and tell us whether that tiger in Life of Pi was made up or ask Kamila Shamsie for the achaar gosht recipe from Salt and Saffron or hang out with Ngozi Adichie and tell her how cool she is. But since we cant call Kamila or Yann or Ngozi (and certainly not Jane) I guess the next best thing is to find other people who get excited about books and, well… get excited about them together.

And that is why I kept stalking DWL facebook posts to ask when we would have a DWL Reader’s Club meet in London, until one fine day the DWL voice replied, ‘When you organize it, my dear’ and I went away skipping and jumping at the thought of a readers’ meet finally happening in London (as did the DWL voice, I am sure).

So for its first meet the DWL Readers’ Club in London (from now on referred to as the London meet) chose to discuss Hosseini. Of course at that point the ‘DWL Readers’ Club in London’ consisted only of me and Sonal (who had been volunteered to co-organise this event) and our choice was the result of some careful thinking.

Me: ‘Who should we talk about?’

Sonal: ‘Hosseini.’

Me: ‘Why?’

Sonal: ‘I just got his latest book.’

Me: ‘But DWL Dubai is already starting off with that one. Okay, okay… let’s be different and talk about all his books!’

Sonal: ‘Haan. Good idea. We could talk about what people think about the characters he creates.’

Me: ‘Haan haan. Clever.’

Sonal: ‘And look, here is a picture of all three of his books together that we could use to advertise the meet.’

Hosseini seemed to work as we eventually got twenty-four people signed up for the meet. True that some of them didn’t live in London, nor even the same time zone, and most of them shared either one of my last names, but that was all mere technical detail. We were going to have this meet, even if I had to bring my kids to help fill up the seats (although their response to his books had been pretty lukewarm – ‘But mama you can’t really have a thousand suns’).

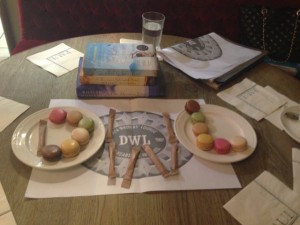

Fast forward to 2:59 pm on the day of the meet and Sonal and I could be found staring forlornly at a plate of macaroons dutifully shaped in the letters ‘D’ and ‘L’ (we used sugar packets for the ‘W’… those macaroons are expensive!). Our back-up plan, if no one came, was to yell ‘free macaroons!’ and snap lots of pictures when people stampeded to our table.

Thankfully people did show up.

I spotted Harsha first, struggling behind the long queue trying to get into the café. I went to bring her to the table, greeting her enthusiastically. She politely asked how I had managed to recognise her, considering we had never met. I shrugged noncommittally (how could I explain that she would recognize people too if she had stalked their page a few times to determine the probability of them turning up at this meet?). And then after Harsha came the others, filling our table to capacity. These included a real writer (yes, yes, the cool factor of our meet went up a notch or two) and a DWL regular who has been to DWL Karachi meets.

I had anticipated that the conversation of a group that had never met before would be full of starts and stops, so had come armed with sheets full of ice breakers. But this was a group of women who were ready to chat. After a few minutes of ‘so which of his books have you read?’ and ‘how do you know about DWL?’ I discreetly dumped my sheets of paper under the table before anyone could spot my lame whose-line-is-it-anyway-type ice breaker questions about characters from the book. A little introduction about DWL, Papercuts, a plea about the Indiegogo campaign, and we were ready to talk Hosseini.

Most people had read his first book, some his second and a couple of us his third book, so the conversation focused on themes of his books rather than specifics (note to self and Sonal: for next meet choose one book so everyone talks about the same writing).

As this was Hosseini, the first word to go around the table was ‘depressing’. For some of us, though, his writing was sad but also showed that life was resilient – his characters went right on living and growing through all the tragedy. We went through the characters in his book, noting how they were impossibly human in their capacity for good and bad. A question we asked was whether the women in his books were stronger than the men. Anqa passionately disagreed, saying that Mariam was shown just as human as her father, for example, in her initial relationship with Laila. We spoke about how the relationship between fathers and sons and their capacity to disappoint each other was a recurrent theme in his books and how legitimacy and gender played into the story lines.

Holly felt that The Kite Runner had the weakest protagonist she had ever come across. Ayesha felt that although Hosseini fleshed out real characters, he didn’t do so well in describing how they felt. Perhaps this was because of his first profession as a doctor: he gave us the diagnosis but let us work out our feelings for ourselves. The doctors around the table nodded their heads vigorously on that one.

Inevitably the conversation turned to Afghanistan and the fact that Hosseini made this country accessible to the world at the right time. We discussed whether he was qualified to write about Afghanistan, a country he left when he was only ten. But all of us around the table agreed (strongly) when Harsha said that it takes one to leave a country to see it and experience it more clearly as she felt about India, having left a few years ago. Perhaps that was why he was able to describe so beautifully what Amir would feel like when he went back to Kabul to find his family home before he went back himself (something he describes as ‘life imitating art’ in the foreword to the tenth edition of the Kite Runner).

We discussed how one’s own personal context has an impact on how one feels about a book. A few of us around the table felt that our threshold for pain was much lower than where it was a few years ago. For books that had recently made us laugh, Moni Mohsin’s and Shazaf Fatima Haider’s work was cited. Sonal wondered if the things that made us sad were universal but the things that made us laugh were more culture specific. I suggested it was also because humorous writing is so difficult – it demands that the writer writes only what the reader wants to read rather than what the writer wants to write.

On the same note, Nigham suggested that the next London meet should be on a lighter book. ‘What?’ I thought, ‘They want to do this again!’ and my facial muscles (which had not sagged throughout the meet) hoisted themselves up even more. Somewhere quieter perhaps, Ayesha suggested, and we nodded as the waiters hovered around us to release space to the Covent Garden crowd, which leant, half frozen, against the café’s doors.

And that is how our first London meet ended: appropriately, with plans about the second. To find out more about when that will be, and what book we will be reading, please email london@desiwriterslounge.net or watch the DWL facebook page. To find out whether any one showed up (again) watch this blog!