As a city, London misses no opportunity to celebrate South Asia. From the London Asian Film Festival in March to the South Asian Literature Festival in November, London’s nostalgic obsession with the Subcontinent persists through the year. But for me and other members of the DWL London Readers’ Club, nothing quite compares to the Alchemy Festival that takes place at the Southbank Centre each year.

The Festival, now in its sixth year, brings together the best of South Asian dance, music, theatre, design, fashion, comedy and literature in a single space. With so many different ways of connecting to the region on offer, the problem with each year’s Festival is deciding which sessions to attend. This year was no different. Running for eleven days from the 15th of May till the 25th, the excess of choice seemed impossible to negotiate: Should we choose to get tickled pink(y brown) by the Alchemedians or find the courage to watch Nirbhaya? Should we attend a talk by Monica Ali in the book club sessions or take a masterclass to learn how to grow Kodu, a Bengali vegetable?

The 2015 Festival formally added another art form to its list of experiences: South Asian street food. For eleven days, the Southbank Centre and its immediate vicinity wafted in the smells of Karachi, Bombay, Dhaka and Calcutta. More than twenty odd stall owners worked to bring together (a hygienic version of) South Asian street food: from fresh coconuts to mango lassi, from the humble bun kebab to the offer of the grand Amitabh tikka.The food added its own feel to the Festival – what can beat the pleasure of hearing writers speak of their characters with a cup of hot masala chai cradled in one’s hands, or the delight of listening to Alchemy Unplugged while consuming a chutney-dripping kebab roll or crunchy papri chaat?

The Festival is special for the members of London Readers’ Club because it not only allows access to our own versions of “home” but because it also allows us to travel to parts of the region that we would ordinarily not see. We were especially excited about the Jaipur Literature Festival coming to London as part of the Alchemy festivities. Even though the Jaipur-on-Thames was meant to be a “mini-taster platter” there were around 21 sessions over two days. Those of us from the London Readers’ Club tried to cover many between us.

One of our favourites was the Shakespearewallahs with Pragya Tiwari in conversation with Suhel Seth and Tim Supple. The ironic reversal in positions – quite common in literary events in London today – was what made this session so entertaining, with Suhel Seth stressing the need to maintain the purity of Shakespeare’s writing by sticking to the prose and pauses of the original plays, and Tim Supple, the producer of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, using Indian actors and languages, talking about remaining true instead to Shakepeare’s genius in taking folklore or popular stories of the present day and reinterpreting them.

The session Divide and Rue: the Partition of the Indian Subcontinent we found controversial. Partition is always an emotional topic, and became more so because the entire panel – made up of Dilip Hiro, Navtej Sarana and Andrew Whitehead, moderated by Urvashi Butalia – did not have a single person from the Pakistani or Bangladeshi community… something the audience criticized directly. And despite the best efforts of some of the panel members to direct the conversation to the question of how best to preserve the narrative about partition, politics and (visa) policy took over.

The Jaipur Festival also offered an opportunity to listen to VS Naipaul talk about his craft and career. Nigham, who attended the session said, “It was a memorable experience watching a Nobel-Prize-winning author speak about his life and memories. Listening to Naipaul talk about his work, you get the overriding sense that writing has been a tortuous process for him.” When asked in the session how he started writing, Naipaul said he’d been asked to give up his first job because he was not very good at it. Out of this rejection, this “great gloom” as Naipaul called it, came the idea that he might write about himself and his background, which, he stated, “is hard to do as you don’t discover facts about yourself readily.” He had a lot of trouble getting started (“Those were dark days for me”). Although tragic for Naipaul, it may be oddly reassuring to a new writer that writing can be an unhappy process for the best of us.

In another interesting session, Clueless: Season of Crime, Somnath Batabyal spoke to Nils Nordberg, Alison Joseph and Ashwin Sanghi about crime writing. Most of the audience’s questions were directed to Ashwin’s experiences about crime in India. Before the session, I was quite skeptical about whether crime writing would ever be fashionable in a region where “fact” is faster paced and stretches the imagination further than fiction. However, in the discussion, Alison – standing up for the crime writing genre – made an interesting point: that crime fiction is popular because it allows resolution in a way that reality cannot. From that point of view, then, perhaps crime fiction does have a future in South Asia.

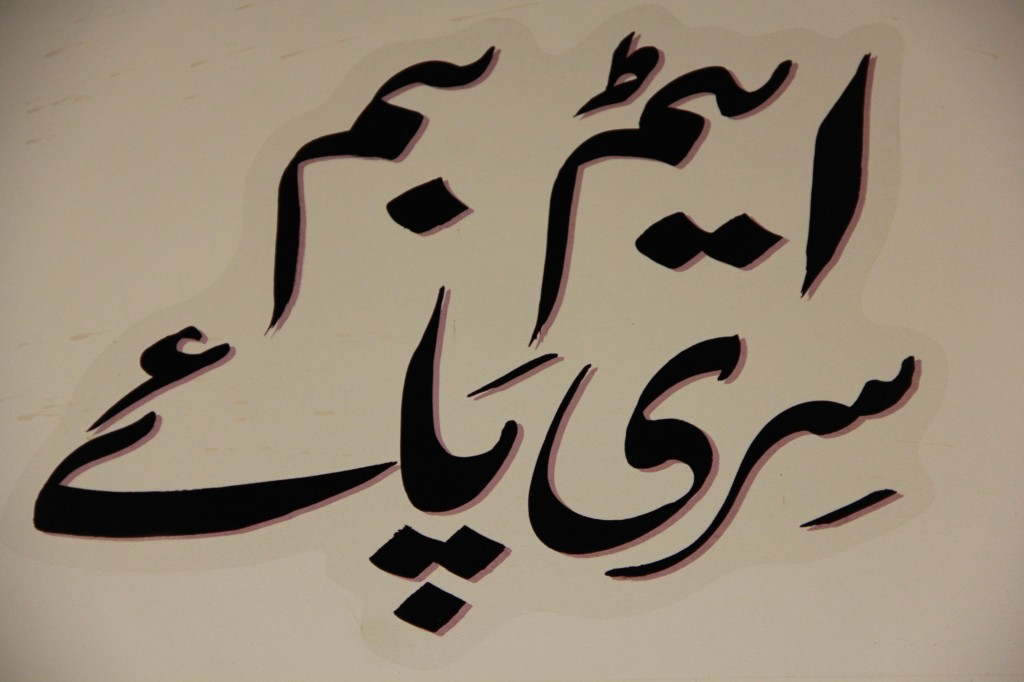

Perhaps the Festival this year allowed a lot of us to seek resolution for some of our feelings in a similar way. The 2015 Festival included Dil Phaink, an audiovisual showcase by PeaceNiche, presenting Pakistan’s street culture, cult cinema, visual memory, and matters of the heart. The fact that Sabeen Mahmud, the driving force behind this peace exhibit, had been fatally shot down in Karachi just weeks prior, gave it an entirely new meaning. This was best articulated by Shazaf Fatima Haider, who had moved to London the very day of Sabeen Mahmud’s assassination.

“To say that I was devastated would be an understatement,” Shazaf said. “T2F, for me, was a large part of Karachi, and it seemed that the part of home that I had loved and cherished, the part that filled me with pride, had suddenly disappeared the minute I had looked away. I caught up on the three days of news that I had missed while moving. I read every post and gazed at every photo of Sabeen – her face was all over the media. I couldn’t believe this brave, wonderful woman whom I’d had the good fortune to know, was no longer alive. I realized that the only way that I could pay my tribute was to go to the PeaceNiche exhibition. A novice to the London transport system, I braved the journey by tube and got to the exhibition, saw signs of my beloved city and the exhibition itself, wrote on the Dukhi Dewaar, and talked at length to a clearly devastated Chand. We both spoke about her for over an hour.

“The exhibition was like Sabeen: eclectic, creative, thought provoking, hilarious. I watched the compilation of news videos that traced Pakistan’s military and political history, with juxtaposed scenes that formed an ironic comment of the compiler – who happened to be Sabeen herself. Little did she know that the montage would end with pictures of her own death – a lone kola puri nestled among shattered glass. I prayed for her then, and for her mother, whose strength has me floored. In the exhibition was a small stall that had a caricature of Sabeen riding away in her scooter, an impish smile on her face. In Karachi, little acts like riding a scooter and being the only woman doing so, are in fact the hugest acts of courage and gumption. Sabeen had gumption in droves and she urged all of us to speak in our different voices and tell our different stories. She is my hero and I salute her.”

This particular exhibit peaked with a concert by Overload on 21st May. Mariam, who like many others attended the event as a tribute to Sabeen said, “The concert, like the festival, blended the familiar with the foreign perfectly. It showed that you can understand emotion from a language you can’t speak, and dance to a music you don’t understand. The concert was respect, passion, drumbeats, colour. It was warm and eclectic. And I am sure Sabeen smiled a million times from somewhere above, hearing the beat while reading all the messages people filled on London walls in her honour.”

The Alchemy Festival ended on Monday, 25th of May. Now we wait for the next festival and all the opportunities it brings to connect to our idea of home, connect to each other and to connect to better versions of ourselves.

Dil Phaink by PeaceNiche, Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Zainab at Dil Phaink by PeaceNiche. Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Pragya Tiwari in conversation with Tim Supple and Suhel Seth. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

“Revolutions of Rising Aspirations”, a session at Alchemy Festival, 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Sidin Vadukat and Rajdeep Sardesai, Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Dil Phaink by PeaceNiche. Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Dil Phaink by PeaceNiche. Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Dil Phaink by PeaceNiche. Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Dil Phaink by PeaceNiche. Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Dil Phaink by PeaceNiche. Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Dil Phaink by PeaceNiche. Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Dil Phaink by PeaceNiche. Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Dil Phaink by PeaceNiche. Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Dil Phaink by PeaceNiche. Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Dil Phaink by PeaceNiche. Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Dil Phaink by PeaceNiche. Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Dil Phaink by PeaceNiche. Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Dil Phaink by PeaceNiche. Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Dil Phaink by PeaceNiche. Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Dil Phaink by PeaceNiche. Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Dil Phaink by PeaceNiche. Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Dil Phaink by PeaceNiche. Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Divide and Rue: the Partition of the Indian Subcontinent. Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Divide and Rue: the Partition of the Indian Subcontinent. Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

The joy of a bun kebab in London, Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Bodyline. Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Pulse and Bloom, Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

South Asian street food on offer at the Alchemy Festival 2015 including the “Amitabh”. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

An Indian Street on Southbank, Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.

Dil Phaink by PeaceNiche, Alchemy Festival 2015. Photo by Sumera Nizamuddin.