Papercuts magazine’s Reportage Editor Hassan Mustafa speaks with Kanishka Gupta, CEO and founder of Writer’s Side, for a better understanding of the literary agent’s role in the publication industry and the emerging trends in poetry, fiction and non-fiction publishing in South Asia.

Hassan Mustafa (HM): You are often termed as ‘the only agent making an impact’ – how do you see yourself? Tell us how you decided to pursue this career path?

Kanishka Gupta (KG): I am an accidental agent. I actually began my career as a writer after my plans for higher education went for a toss. I was restless, delusional and fame-obsessed; however, after, several years of rejections, heartbreak and unemployment, I managed to connect with a Jaipur-based agent who in turn connected me with the novelist Namita Gokhale. She sowed the seed of entrepreneurship in me – saying that I was meant for bigger things. Seven months after our first meeting, I started Writer’s Side with an investment of Rs.7000.

Over the years, I believe I have emerged as the only agent in South Asia who gets along well with every single publisher, multinational or domestic, big or small. Last year, we sold 100 books to mainstream publishers – 25 were acquired by HarperCollins India. In 2016, we’ll cross 180 deals if not more, with more than a dozen sales to at least five top publishers.

I am happy with the domestic growth, what I am not happy with is my agency’s progress in the UK, US and European markets. I would like to represent more international literary fiction and non-fiction as well. But I also believe that everything happens when the time is right.

HM: Can you describe the process – from the selection of manuscripts to the publishing stage?

KG: I used to rely on unsolicited submissions when I’d just started, since I was not well known, but now I get most of my authors through referrals or within my own circle of 450+authors. We still go through and sign unsolicited submissions, but not more than 6-8 in any given year. I also approach a lot of promising authors on my own with book ideas – I feel they are most suited for. I select, edit and pitch all non-fiction myself, and rely on my editor Achala Upendran for the fiction submissions.

The period from selection to acceptance by a publisher really depends on the submission and the time of year in which it is submitted. Usually, I manage to get offers or responses from all the top publishers quite fast. Decisions on fiction submissions can take more than a couple of months since publishers usually like to get everyone on board before deciding to make an offer. The time period from acceptance to publication is usually 8-12 months unless the book is a very time-bound one.

“It can be safely said that Subcontinent’s publishing has been playing second fiddle to UK and U.S. publishing and the only genres that are immune to this influence are commercial fiction and books written by local celebrities and public figures.

HM: From among the authors you have worked with, whose works do you think have truly broken taboos?

KG: Some books that stand out for me are, Shreyas Rajagopal’s Saltwater – an adept, unflinching unmasking of the depravity of the children of Mumbai’s elite – it has a Bret Easton Ellis feel to it and was also published in Germany by a major publisher. All of Anees Salim’s books – the first writer I represented – stand out because of their milieu, the memorable characters, the intricate world building and the understated humor. I am also happy with; Kashmiri Pundit/writer Siddharatha Gigoo’s Commonwealth Prize-winning Fistful of Earth, Ruchira Gupta’s Emmy-award-winning, River of Flesh – which is a hard-hitting collection of translated fiction focusing on prostitution in the subcontinent.

I also managed to get the controversial writer Aroup Chatterjee; a mainstream publisher for his exposé of Mother Teresa more than 20 years after the book was self-published.

A few forthcoming books I am excited about include: Sabyn Javeri’s masterful political thriller Nobody Killed Her, Arnab Ray’s The Mahabharata Murders, Anita Sivakumaran’s literary novel The Queen, Dominic Frank’s travelogue The Nautanki Diaries, and the translation of an outlawed Urdu author by Reema Abbasi among others.

“The only genre that is growing and thriving is local non-fiction – books on politics, current affairs, sports, and cinema. Unless local influencers change the current trend – with activities like Oprah’s Book Club – things are not going to change for the better.

HM: In a recent interview, you asserted that writers who don’t have endorsement from the West have a similar sales pattern regardless of the fact that they are from Pakistan or India. What in your view do emerging South Asian writers have to do to procure themselves a global audience?

KG: Not a single Indian or Pakistani writer of literary fiction has made it big just by being published in the subcontinent. All of the successful South Asian writers were either nominated for the Booker/Pulitzer prize or were involved in highly publicized global deals involving obscene amounts of money. Even though, unlike Pakistan, India has its own share of major prizes for English fiction and non-fiction like the Crossword Prize, Hindu Literary Prize, and the Shakti Bhatt prize, the truth is that these do nothing for the recipient in terms of sales. The DSC Prize for South Asian Literature, for instance, carries a huge purse but I am not sure it means anything to the common book buyer.

I know of several prize winners who haven’t even managed to sell out their first print run, while The White Tiger sold almost 200,000 copies on the strength of its unlikely Booker Prize win. And I am certain that the latest Intizar Hussain translations done by Rakhshanda Jalil wouldn’t have had such an easy path to publication were it not for his Man Booker International shortlisting.

At times, I have used this western endorsement and acclaim myself, to bring some of my Pakistani writers to a publisher’s attention. When I pitched Ali Akbar Natiq’s debut short story collection, I emphasized the publication of one of his stories in Granta.

It can be safely said that Subcontinent’s publishing has been playing second fiddle to UK and U.S. publishing and the only genres that are immune to this influence are commercial fiction and books written by local celebrities and public figures.

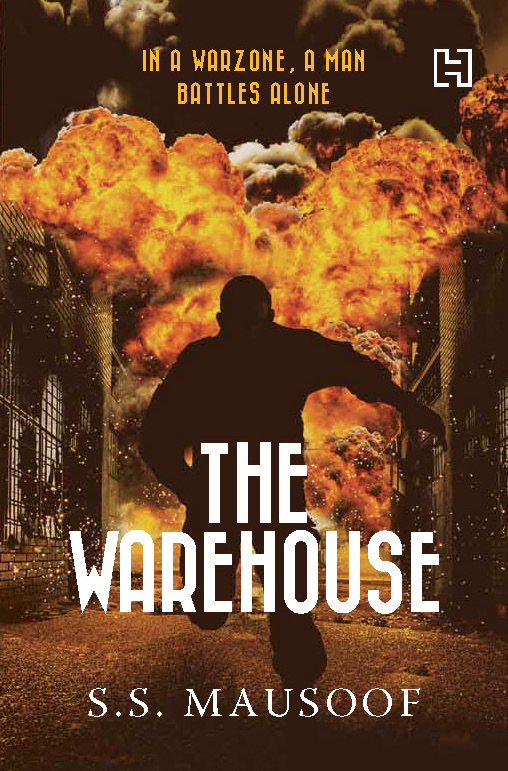

I think under the given circumstances, writers just have to keep trying for a UK or a US deal. The good thing is that now Indian agents can help writers achieve this seemingly distant goal. Just as an example, I was able to sell Pakistani writer S.S Mausoof’s stylish crime noir The Warehouse not only in the UK but in France as well.

HM: How do you see the landscape – sales, reading patterns, reception of writers, genre preference, and access to material – changing for poetry, fiction and nonfiction in South Asia in the future?

KG: I don’t know of any editor other than Karthika VK of HarperCollins India who has a dedicated poetry list. Many publishers don’t even consider poetry as per company policy and only classics like works of Faiz, Ghalib or Aga Shahid Ali or (heaven forbid) something by a Narendra Modi or a Bollywood star will find takers! That’s why I was delighted to be able to place 22-year-old Pakistani writer, Asad Alvi’s translation of Sara Shagufta’s poetry to Speaking Tiger within two days of submission. But then again, Shagufta’s work can be considered under the banner of Classics.

The good news is that poetry is gaining currency and purely merit-based publishing platforms have come into existence. The (Great) Indian Poetry Collective is one of them, founded in 2013, which has been publishing up to three books a year. Additionally, due to the nature of the set-up, a lot of serious and emerging poets are going to opt for this route – one of the winners, Rohan Chetri, former Hachette editor and poet is already making waves in India and abroad.

“I don’t think that a writer should do a book keeping in mind the market value or ‘marketability’ of his/her book but he/she shouldn’t be unrealistic and delusional either – since some genres have a wider acceptance than others.

On the other hand, literary and mid-list fiction faces the same fate as poetry and short-stories, since erstwhile standard print run of 2000 copies is no longer feasible for many publishers and very few merit a 5000 copies first run. Additionally, the UK and U.S. publishers aren’t accepting work the way they used to.

The only genre that is growing and thriving is local non-fiction – books on politics, current affairs, sports, and cinema. Unless local influencers change the current trend – with activities like Oprah’s Book Club – things are not going to change for the better.

HM: What advice do you have for aspiring writers? Do you feel they should have a basic understanding of the “market value” of what they plan to write?

KG: Book publishing is a business first and foremost, and editors and publishers are accountable to their bosses for the success and failure of every single book. However, I firmly believe you should write only if you are passionate about your craft and have a worthwhile story to tell. One has to understand that a lot of things have to come together seamlessly to make a successful book, including writing skills, an original story idea, craft, discipline, perseverance, right timing, and of course, luck. Otherwise, every other writer would be rolling in awards and riches.

So, I don’t think that a writer should do a book keeping in mind the market value or ‘marketability’ of his/her book but he/she shouldn’t be unrealistic and delusional either – since some genres have a wider acceptance than others.