Tishani Doshi is the author of five books of fiction and poetry. At 26, an encounter with the choreographer Chandralekha led her to an unexpected career in dance. In 2006, her first book of poems, Countries of the Body, won the Forward Prize for best first collection. She is also the recipient of an Eric Gregory Award and the winner of the All-India Poetry competition. Girls are Coming out of the Woods is her third full-length collection. She lives on a beach in Tamil Nadu. More of Tishani’s work can be found on her website.

In this interview, Tishani talks about her upcoming poetry collection Girls are Coming out of the Woods (HarperCollins India, 2017) and much more.

Michelle D’costa (MDC): In an interview with PORT about the poem form, you say, ‘It’s just the sense of a pure form and it’s mysterious, like I don’t know exactly what makes a poem a poem – why is it not something else, why is it not cut-up prose? It’s just arranging words on a page differently… and it’s to do with that primal sound, with the beat, with the metre. There’s something very old about it.’

You are a dancer. A dance pose of yours reminded me of a contortionist. Is a poem ‘a contortion of words’ to you?

Tishani Doshi (TD): On a very literal level of play—to contort, to bend, to twist out of normal shape, yes, there can be playfulness in poetry, and in this collection specifically, there’s more play than in previous collections. But I don’t see dance or poetry as contortion. I see it as a release of movement, of stillness, of what happens between. And so if we wanted to talk about poetry in terms of shape, then I think of it as something more fluid than arriving at certain poses.

MDC: In your poem ‘Love Poem’ that I read online, the line ‘It might be that you walk out’ gave me the impression that the man had actually walked out of the page. The effect was beautifully devastating. How do you decide on enjambment in a poem?

TD: It’s one of the things I love about poetry—deciding where the line ends. There’s that lovely apocryphal story about Oscar Wilde, who said, I spent all morning taking out a comma, and I spent all afternoon putting it back, or was it the other way around? Anyway, as writers, there’s a lot of time spent putting commas in and out, but also, deciding on word endings and just generally staring out of windows.

You cannot live life in nonstop crescendo. You will stagger and fall. At least for me, it’s in the movement from slow to fast that life is lived, that books are written.

MDC: You use simple language in your poetry. It makes non-poetry readers approach your work without apprehension. What is your view on verbose poetry?

TD: I’m not averse to using non-simple words. One of my favourite words is obfuscate! There’s a difference, though between using complex words and being verbose, which is to use more words than needed, which is really anti-poetry. Poetry to me is all about distillation so it’s about finding the right word. I’m not sure I buy the argument about using simple language, because why do those words exist if we can’t use them? I was talking to a poet friend of mine who said that Arabic had 30-40 words for sand, 70 for water! Such richness, such precision. Every language has its own treasure chambers and I feel the poet needs to excavate those. I collect words, I keep lists. If I come across a word I don’t know I sometimes look it up, and sometimes let it just float over me with whatever I think it means. I’m not afraid of words and I don’t think readers should be either. A word that I’ve never used in life but which I’ve used in a poem for instance, is philtra, which is the plural of philtrum, which is the vertical groove between the base of the nose and the border of the upper lip. After a storm all the dunes in the sand were puckered up like philtra—and once you see it that way, you can only use that word.

MDC: Your novel Pleasure Seekers was long-listed for the Orange Prize in 2011 and shortlisted for The Hindu Best Fiction Award in 2010. It took you eight years to write it. I watched your TED talk Luxury of Slowness. In this hyperlinked fast-paced world, a person looking for calm can approach your work. In an article of yours you talk about the slowness in the way you live also: ‘Being in a quiet place with few distractions is good for writing. It’s magic for the nervous system. Everything shushes.’ Any comments?

TD: Slowness is something we teach ourselves. I don’t think it’s a natural instinct at all. I live the way I do because I can stand it. But sometimes, after ten days, I need the pulse of a city, the mad horrible push of humanity to remind myself that I’m part of it. I’m interested in slowness not in and of itself, but in its contrast to speed. Because I do love speed. Some of the best moments in my life have been sitting behind a motorbike with the wind rushing through my hair (eeks, no helmet—bad!), skydiving (never again), running till I thought my heart was going to burst out of my chest. But as I say in my TED talk, speed is only really impressive when we arrive there after slowness. I see it in musical terms. You begin with the alaap, you spend most of your time in this slow, abstract place, you move through vilambit, jor, jhala, collecting force and textures and speed along the way, and it is in this progression that the music unfolds. You cannot be in crescendo mode right from the start. You cannot live life in nonstop crescendo. You will stagger and fall. At least for me, it’s in the movement from slow to fast that life is lived, that books are written.

Tishani Doshi. Photo credit: Peter Åkesson.

MDC: Your novel is semi-autobiographical. How about your poetry? I loved your poem ‘My Grandmother Never Ate a Potato in Her Life’ from your upcoming collection. It made me wonder about your paternal grandmother as your father is Gujarati (Jain).

TD: The question of biography is endlessly fascinating for readers and endlessly irritating for writers, mostly because I think it implies a lack of imagination. If you admit that you draw from life then it’s thought of as kind of lazy—What? You didn’t make anything up? As if it’s some kind of cut and paste job. Whereas anyone who’s ever written knows that writers are constantly taking from life, theirs or other people’s, and there’s a process during the writing when that gets transformed into something else, and that transformation is the most interesting part of writing. My paternal grandmother died when I was quite young, and as far as I know she never ate a potato in her life. I’m not sure if it’s true, but does it really matter? The poem is its own truth. It goes beyond my grandmother and lands in an entirely different place.

In my poems, it’s all very personal, but I’m also asking the reader to look into this experience of mine, because most people have a version of this—some person that they are fiercely protective of, some love that always needs more.

MDC: In March, you spoke to India Today about growing up with a brother with Down Syndrome. In your poem ‘Summer in Madras’ from your upcoming book you describe family members reacting to the heat and of all, ‘the brother? Brother is most lackadaisical of all’. Does the reader get to meet your brother briefly here?

TD: My brother has always been a presence in my poems, hovering on the sidelines, and in this collection he moves closer to the centre. This is not disconnected to the fact of both of us growing older, my sense of responsibility increasing, and with it a sense of fear and dread and all the rest of it. When I was growing up there was a real invisibility around disability. People would stare at my brother because they just hadn’t seen someone with Down Syndrome. That staring was so disconcerting. Even now, when my parents travel with him, some people are amazed that they bring him along this way. So, it’s about visibility, and questioning how a society treats people with disabilities, how much space they give to them, how they can be trained to look differently. In my poems, it’s all very personal, but I’m also asking the reader to look into this experience of mine, because most people have a version of this—some person that they are fiercely protective of, some love that always needs more.

MDC: The title poem feels like a feminist anthem. It is beautiful and disturbing at the same time. How did you conceive it?

TD: I had been reading a lot of stories about violence against women in India, and it was unrelenting. I had this picture of what might happen if all these women and girls suddenly marched out of the woods and it took on a kind of incantatory rhythm, so it’s interesting how you have an idea for something, but when you find the form, that’s when the poem really begins to take shape. Here, the repetition of girls are coming, girls are coming, started to gather force, and I just let it run through.

MDC: Why free verse?

TD: Why not?

MDC: The poems in your new book shift from left alignment to central alignment. How do you decide on it and do visual effects affect the way a reader consumes your poems?

TD: Again, this has to do with play. Most of them are left-aligned, which is pretty standard, but the grandmother poem looks potatoish if it’s put in the centre of the page, which I thought was a nice visual effect.

MDC: If you hadn’t met Chandralekha, do you think you would have been a dancer anyway?

TD: I was a dancer before Chandralekha. My girlfriends and I put on legwarmers way back in the late 80s when you did that kind of thing even in Madras, and danced to “Eye of the Tiger.” I’m never shy of initiating a dance floor, and from the age of three I had also been taking part in dance dramas where I’d be a flower, peacock, prince—that kind of thing. But dance in the way Chandra made me dance, where the body is the most central energy to life? Impossible. It would never have happened.

MDC: If not dancing or writing or interviewing, what would it be?

TD: In college I was studying business and communications, so perhaps I would have had a nice bank job or something. I like to think of myself as a painter. It might not be too late.

I had this picture of what might happen if all these women and girls suddenly marched out of the woods and it took on a kind of incantatory rhythm….

MDC: Your poems cover a wide variety of themes. Do you believe in Plath’s words: ‘Everything in life is writable about if you have the outgoing guts to do it, and the imagination to improvise.’

TD: I think as a writer everything that you experience is game for subject matter. This is the terrifying thing. Nothing is out of bounds. This is why writers are considered such dangerous people. I believe some stories need their time to be told, and it’s all right to wait on those things. Faulkner said a writer’s only responsibility is to his art. “If a writer has to rob his mother, he will not hesitate; the ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ is worth any number of old ladies.” He’s right.

MDC: You are not only a poet who believes in reaching readers with the written word but also the spoken word as you feel poetry is suffering. You say so in your interview with PORT. Do you think initiatives such as The Alipore Post that has carried your poems help keep poetry alive today?

TD: For some time I called myself a poetry evangelist, but now everyone is a poetry evangelist, so I don’t know. I still believe in ushering poetry into whichever space I find because I do believe poetry deserves a larger audience. I think poetry lends itself to collaborations with film, photography, music—so in theory, it should be everywhere. But I also believe that a poem exists first on the page. That can never be displaced. The page is where you can return to again and again. And for all the obituaries that are being written for poetry, it’s been around for a long time, I don’t think it’s going anywhere just yet.

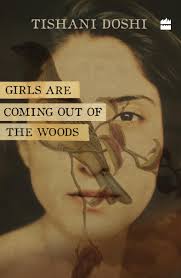

Girls are Coming out of the Woods book cover. Courtesy HarperCollins India.

MDC: It is tough for writers (literary) living in India to earn a living from their writing alone. How do you and Carlo manage?

TD: It’s not easy to make money from poetry and even literary fiction is tough. However we both work as journalists pretty full on. Carlo also teaches a post-grad course, and for many years ,I worked with a professional dance group. There are always projects here and there that come up which pay decently but these are unreliable, in any case uncertainty is something you come to terms with.

MDC: Would you like to give any advice to aspiring writers or recommend any book.

TD: My advice is to read. Read something you know you’ll enjoy. Read something you know you’ll struggle with. Read my book of poems.

MDC: Thank you Tishani for speaking to me and thank you Harper Collins India for providing me with a copy of Girls are Coming out of the Woods.

Michelle D’costa edits fiction for Jaggery Literary Magazine. Her poetry/fiction has been published in The Madras Mag, The Bombay Literary Magazine, Open Road Review, Eunoia Review among others. She blogs at michellewendydcosta.wordpress.

Terrific interview! Good job Michelle!